The career transformation of Charlie Morton has become a polarizing topic, both among the Pittsburgh Pirates’ fanbase as well as the media landscape on both the local and national levels.

Morton, who was 2-12 with a 7.57 ERA last season, was sent to the disabled list in late May and then assigned to Class AAA Indianapolis to regain his confidence and salvage his career. He was recalled in late August and recorded a 4.26 ERA in his last six starts.

Pirates minor league pitching coordinator Jim Benedict sat down with Morton during Spring Training this year and proposed something that would change everything: lowering Morton’s delivery from overhand to a three-quarters diagonal delivery and adding a sinker to his mix of pitches, totally revamping his pitching motion and repertoire to resemble that of Philadelphia Phillies ace Roy Halladay.

Morton has been spectacular so far this season with a 5-2 record and a 2.61 ERA in nine starts. Seven of those starts have been quality starts (at least six innings with three or fewer earned runs allowed). However, in those seven starts, the Pirates are only 4-3, scoring four runs or less in all three losses.

While the video evidence of the similarity between Morton and Halladay is pretty self-explanatory, some are still skeptical of whether or not this trend will continue. (Many of them reside in the Pittsburgh area, where skepticism abounds in droves these days.)

But I present to you the following examples: two men who experienced situations similar to Morton’s and witnessed a career resurgence after being demoted to the minors to make some significant changes.

Pitcher A, age 23 at the time, had a 4-7 record with a 10.64 ERA in 67.2 innings in the majors before being sent all the way down to Class A at the beginning of the following season to reconfigure his delivery, adding a repertoire of pitches that had both vertical and horizontal movement. After making said adjustments he slowly rose through the system to return to the majors and post a 5-3 record with a 3.16 ERA and 96 strikeouts in 105.1 innings by the end of the year.

Since then he has a winning percentage of .686, a 3.01 ERA, two Cy Young Awards and has been named an All-Star eight times.

Pitcher B, then 25, was a starter having already undergone Tommy John surgery to repair a torn ligament in his torn elbow. His results as a starting pitcher in the major were mixed, causing him to be shuttled back and forth between the big show and Triple-A.

Patience began to wear thin, insomuch that his team’s general manager was ready to trade him to the Detroit Tigers for David Wells, but changed his mind at the last minute after learning of a sudden spike in the pitcher’s velocity, adding up to 6 mph to top out as high as 96. While nobody could explain the reason for the change in velocity, the pitcher himself simply called it an act of God.

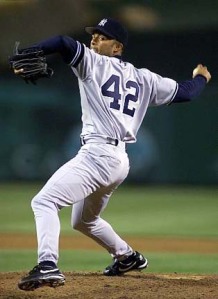

He eventually returned to the major league club and threw a two-hit shutout against the Chicago White Sox with 11 strikeouts. However, his success in relief during the postseason convinced the team to convert him to a full-time reliever the following season. He eventually became the team’s closer and never relinquished the role.

One day, while playing catch with a teammate, he accidentally discovered the grip for a cut fastball that moved very sharply toward left-handed hitters. After trying and failing to regain the straight motion his fastball had before, he finally embraced it and began using the pitch in games.

Since the year he began throwing the cut fastball, he has recorded a .559 winning percentage with a 2.02 ERA and 567 saves and has been named to 11 All-Star games.

All it took was a small adjustment for Roy Halladay to eventually become the man simply known as "Doc."

Player A is Halladay in 2000. Pitcher B is Mariano Rivera in 1995.

Which leads me to this question: if these two pitchers can undergo the kind of changes they’ve made and enjoy success because of them, why can’t Morton?

Of course, the obvious answer is sample size. Nine starts with a new delivery does not a dominant pitcher make, which we all should understand. (For the record: those who quote sample size like it’s some cure-all to explain every sudden phenomenon, we non-smug, less-than-know-it-all baseball fans find you quite annoying. Moving on…)

A mixture of divine intervention and one mistake grip helped make "Mo" one of the best closers in the history of the game.

But if such an improvement can be made by Halladay and Lee to become successful and dominant pitchers, who’s to say the same thing couldn’t occur with Morton? Because he’s a Pittsburgh Pirate and not a Toronto Blue Jay or a New York Yankee?

When you package it with that kind of logic, it sounds pretty ridiculous, doesn’t it?

Let’s get something perfectly clear: I’m not polishing off Morton’s NL Cy Young Award or putting him on the mound for the first inning of this year’s All-Star game in Phoenix (although I do consider it a distinct possibility).

I’m simply saying that if these guys can turn it around, and this guy can go from replacement level utility player to league-leading slugger by making a slight adjustment, than maybe the reinvention of Charlie Morton isn’t that far-fetched of a scenario.

Especially if it’s working.

After all, it wouldn’t be the first time a pitcher learned how to do something better than the way he previously did it and succeeded, would it?